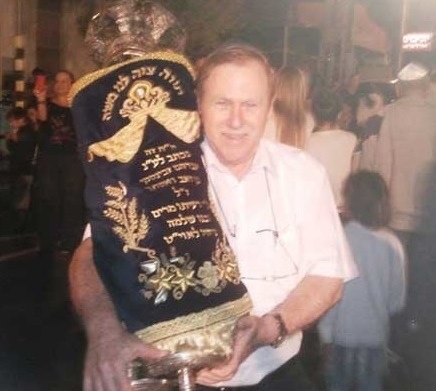

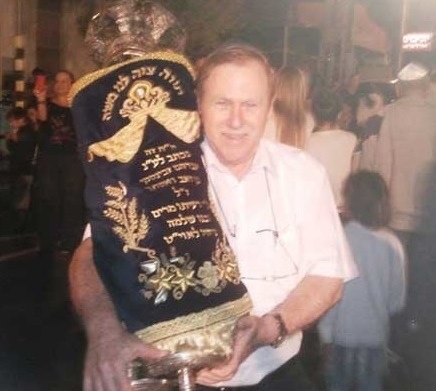

Rosh HaShanah, the Jewish New Year explained by Ari Lipinski

14 Wednesday Aug 2024

ב”ה Rosh Hashana – ראש השנה The Jewish New Year is celebrated with Apple, honey, dates and grapes (wine).

14 Wednesday Aug 2024

ב”ה Rosh Hashana – ראש השנה The Jewish New Year is celebrated with Apple, honey, dates and grapes (wine).